Air quality and health impacts of diesel truck emissions in New York City and policy implications

Blog

Boxed in by pollution: The urgent need for tougher trucking rules to protect communities around warehouses

The growth of online shopping was accelerated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and e-commerce revenue approximately doubled in the United States in the past 5 years. In the neighborhoods where new warehouses have been built to meet this increase in demand, the trend has brought noticeable changes, including emissions from large tractor-trailers that bring containers from nearby ports and vans that collect packages for home delivery. These vehicles emit harmful pollutants including fine particulate matter and a group of gases called nitrogen oxides (NOx).

While the warehouses don’t emit pollution like a power plant, their operations mean that truck traffic and tailpipe emissions concentrate around them. Researchers have detected increases in air pollution in communities where new warehouses have opened.

We at the ICCT partnered with researchers from The George Washington University on a new nationwide study in Nature Communications that helps quantify how much warehouses worsen local air pollution in the United States. The study focuses on nitrogen dioxide (NO2), which is associated with new asthma cases in children, respiratory symptoms such as coughing and difficulty breathing, and other adverse health impacts. NO2 emissions also lead to the formation of fine particulate matter and ozone in the air, which increase the risk of dying prematurely from heart and lung diseases, cancers, and other conditions.

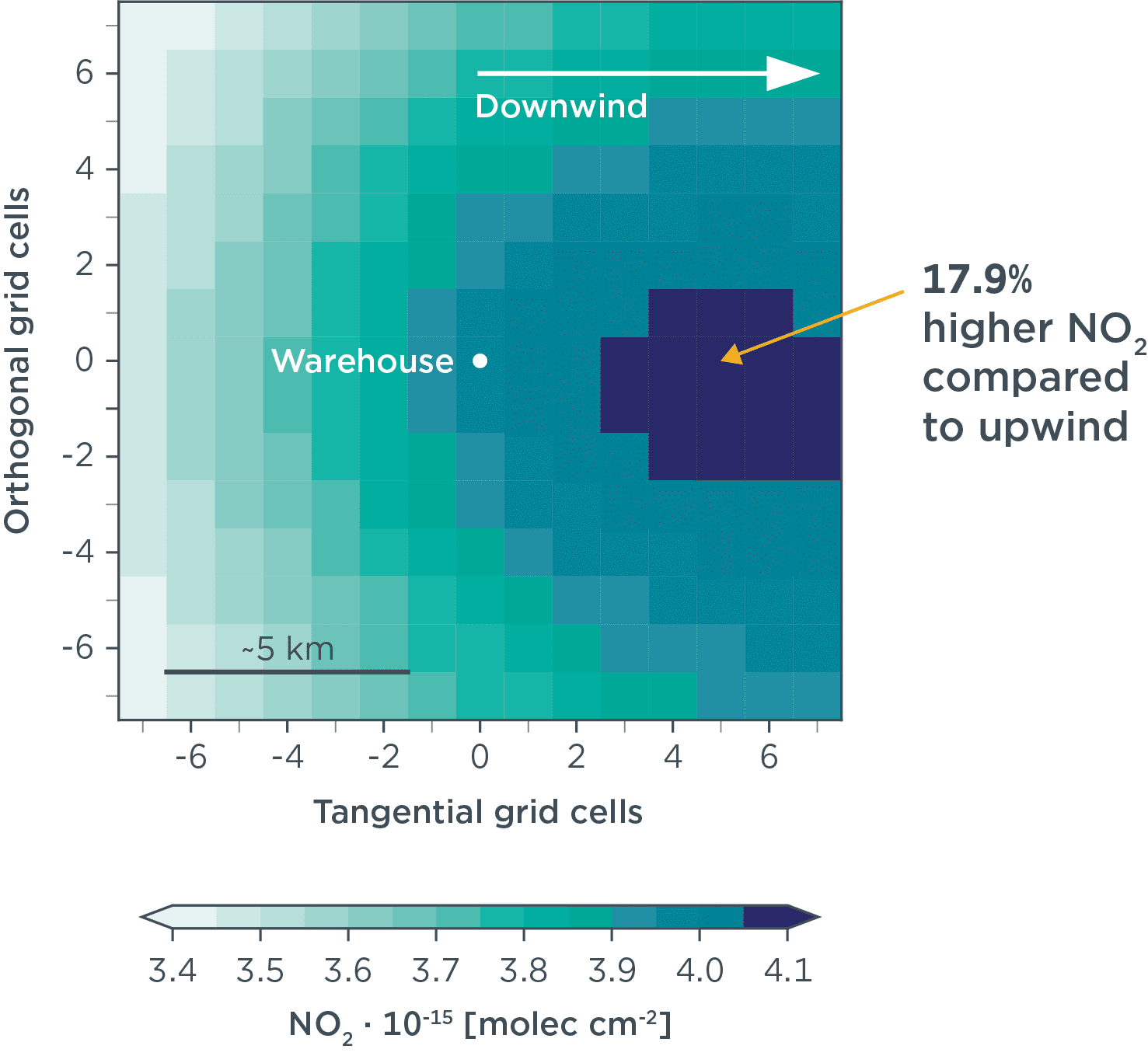

Our study analyzed NO2 satellite data along with a database of nearly 150,000 warehouses in the contiguous United States. The figure below illustrates the pattern in annual average NO2 pollution around a warehouse, averaged across all locations. It shows that there is a spike in annual NO2 of nearly 20% associated with warehouses. The highest NO2 concentration is around 4 km away from the warehouse in the direction of the wind. Additionally, larger numbers of loading docks or parking spaces were associated with more truck traffic and higher levels of NO2.

Figure. Annual average NO2 concentration in 2021 from TROPOMI satellite data averaged over all warehouses in the contiguous United States. Source: Kerr et al. (2024).

Like others, our study also found that census tracts with greater numbers of warehouses tended to have higher shares of residents of color. This aligns with results from previous studies which showed that racial and ethnic inequities in NO2 exposure are largely attributable to diesel truck traffic. Clearly, warehouse-related truck emissions are important to understand when taking action to address air pollution exposure disparities.

Addressing the issue requires action at multiple levels. At the federal level, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently finalized standards that will reduce emissions from new trucks starting in model year 2027. Under these, new engines sold by manufacturers must meet NOx emission limits more than 80% below current levels. Additionally, the Phase 3 greenhouse gas rule, finalized in 2024, will encourage the deployment of more efficient technologies like hybrids and zero-emission vehicles, further reducing NOx emissions from trucks.

At the state level, California’s Advanced Clean Trucks and Advanced Clean Fleets rules require manufacturers to transition to 100% zero-emission sales for medium- and heavy-duty vehicles by 2036. The Advanced Clean Fleets rule also includes a zero-emission drayage registration requirement that will accelerate the adoption of cleaner vehicles at ports and warehouses. Both EPA’s greenhouse gas rule and the California Advanced Clean Fleets rule face legal challenges, but these rules need to stay in place to support the transition to cleaner vehicles and reduce air pollution near warehouses.

Regulations can also directly target warehouse-related pollution. The South Coast Air Quality Management District in California implemented an indirect source rule that requires large warehouses to reduce pollution, and credit is awarded for actions like transitioning to zero-emission and near-zero-emission trucks and installing charging infrastructure. New York City recently announced plans to implement a similar policy.

Lastly, addressing this issue requires action from both the private sector and regulated electric utilities. Amazon, the largest player in the e-commerce space, has committed to deploying 100,000 electric delivery vans by 2030. While a significant step, commitments to end diesel drayage contracting by 2030 and work toward implementing zero-emission service contracts with logistics operators and warehouse owners, and installing charging infrastructure at warehouses, would further demonstrate industry leadership. Prologis, the largest owner of warehouses in the United States, pledged to install 900 MW of charging capacity at its facilities. Simultaneously, electric utilities proactively planning grid upgrades and streamlining permitting for necessary charging infrastructure can help ensure the success of these initiatives.

Emissions from trucks have declined substantially in recent years thanks to regulations requiring more advanced emission control technology. With a nearly 50% increase in freight tonnage moved by trucks projected over the next 30 years, the new rules from EPA and California are key to continuing to make progress. The private sector, electric utilities, and other local rules also have important roles. The status quo is simply not enough. A commitment to delivering clean air requires action to address warehouse-related truck emissions.

Author

Related Publications

Estimates the impacts of transportation sector emissions on ambient PM2.5 and provides a detailed picture of the global, regional, and local health effects.