They say that however much the times change, the essentials of the game of rugby stay the same. Ex-internationals turned pundits say it a lot in their television commentary, so it must be true, right? The unfortunate recent history of the Wallabies would suggest that this is no longer the case – if indeed it ever was.

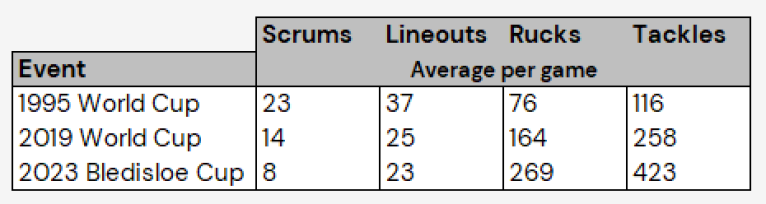

The game itself is barely recognisable now, even from the first World Cup of the professional era back in 1995. Here is a comparative time-line, beginning with some key areas from that tournament, traced through to the last World Cup in 2019, and on to the latest Rugby Championship game played at the Melbourne Cricket Ground on Saturday:

The character of the game has changed, and it will never return to the rosy-glow nostalgia of amateurism, or even to the pioneering spirit at the changing of the guard in 1995. For better or worse, things will never go back to the way they were.

The latest edition of the Bledisloe Cup contained half the number of set-pieces, and between three to four times as many rucks built and tackles made as the tournament average back in 1995. Australia was a world champion team entering that competition, but lately it has been struggling to keep up with times.

For the first time since 2018 and only the second time since the Rugby Championship came to exist in 2012, the Wallabies finished bottom of the table in tries scored, with only seven mustered from their three matches. Whatever Australian teams could or could not do in previous generations, they always knew the way to the goal-line.

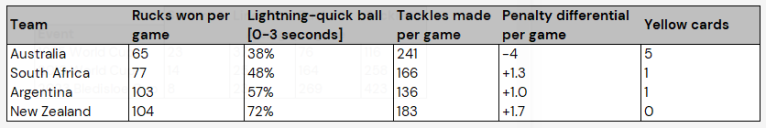

Here are some relevant stats from the 2023 Rugby Championship:

Australia built the fewest number of rucks per game in the competition, and produced the lowest proportion of lightning-quick ball from them. That in turn committed the Wallabies to making 79 tackles per match more than the average among the other three nations. The ‘cascade effect’ is a worse penalty differential, and far more yellow cards than anyone else.

The Wallabies ‘enjoyed’ an average of 39 per cent possession and 41 per cent territory and they only scored one try from four-plus phases, while conceding 10 themselves from precisely those situations. Half, yes half of all the 44 tries scored in the tournament came from sequences lasting four phases or more. Is possession rugby dead, as Eddie Jones proclaimed so confidently before the start of play? The facts say ‘No’ and it is a resounding rebuttal indeed.

If you were to conclude that Australian rugby is somewhere between a rock and hard place, you would be right. The weak five-team system does not equip any of the sides in Australia to play for long periods with ball in hand, and the one franchise which embraces that approach, the Western Force, has no representation at all at national level. The Force have the right idea but lacks the talent to make it stick.

Eddie Jones’ post-match presser was an eloquent one-man dialogue between the spoken and the unspoken; between what was said, which was usually positive, and what was either left unsaid or afforded less airtime, which was not:

“We wanted to show that this was a new team, but [there is always a but]… Our first 20 minutes we showed what we are capable of…

Skipper Tate McDermott sat grim-faced beside his coach, squirming in the gap between the twin realities.

“I really liked the way we came out in the first 20 minutes – and the first 15 minutes of the second half as well… [but] We could not convert that into points.

“The team is a work in progress, but what I liked is the way we took on the All Blacks tactically in the first 20 minutes.

“If you arrived from Mars and watched the first 20 minutes, you would probably think the team in gold was the stronger team … but you’ve got to be able to do it for 80 minutes.”

As Eddie’s stream-of-consciousness rolled on, his skipper Tate McDermott sat grim-faced beside his coach, squirming in the gap between the twin realities. Immediately after the end of the match, Tate had offered a far more forthright appraisal of proceedings to Morgan Turinui: “83,000 people turned up tonight to support us, and we did not give them much.” The truth hurts.

The Australian coach did have some straws to grasp at – not enough to weave into a lifeboat maybe, but sufficient to at least look out to sea with rather more optimism. For the first time in the second Eddie era, Australia went beyond three figures in rucks set on attack (117) – even if that figure was 35 shy of the number set by their opponents; they pilfered six balls from the New Zealand breakdown – even if it still left the All Blacks with a healthy 96 per cent plus retention rate overall; the green-and-gold penalty count dropped down into single figures for the first time (9) – even if there were 20 minutes spent with only 14 Australians on the field due to yellow cards.

The ‘fixes’ somehow only highlighted the magnitude of the task, and there is an uncomfortable sense that the new Australian head coach is only now realising the true proportions of the job he has undertaken. The hope of a 7-5 lead established in the first quarter dissolved into a 33-0 deficit over the other three.

Both the seeds of hope for improvement in the future, and the underlying issues with their growth and maintenance were present in that opening salvo, and nowhere were they better illustrated than in the performance of the young gun at No 10, Carter Gordon.

As Eddie Jones rightly said, Gordon is the best young prospect in Australia at the spot, but he is a ball-handler, a line-challenger and a gap-spotter. He cannot be easily shoe-horned into the three-and-out kicking game that his coach said he wants. His first sand-wedge, on third phase after a kick return, was spooned straight up in the air:

The All Blacks gleefully demonstrated exactly how a good kicking game should work off the receipt by Mark Telea. First Gordon’s opposite number Richie Mo’unga found the sweet spot in between the Kiwi chaser (Will Jordan) and the Aussie catcher (Andrew Kellaway), then Aaron Smith sent Australia (and Carter Gordon) tumbling all the way back to their own goal-line on the very next play:

The whole sequence only lasted four phases, and the All Blacks promptly scored a try on the fifth:

That is low-phase count efficiency for you. One team knows exactly what it wants from the kicking game, the other does not. Gordon’s second attempt at the ‘bomb’ was no better than the first, and it drew another kicking response which was as clinical as it was creative:

By the end of the half, the virus had spread to all corners of Gordon’s kicking game: he had missed touch from another penalty kick, he had missed a goal in a straightforward position in front of the poles, and he had duffed a restart so badly that it barely made five metres, let alone the full ten.

He was not alone. The problem with a automatic kicking formula deployed so early in the phase-count is that it loses opportunities to shift the ball by hand when they present themselves. From that point of view, it is eminently un-Australian:

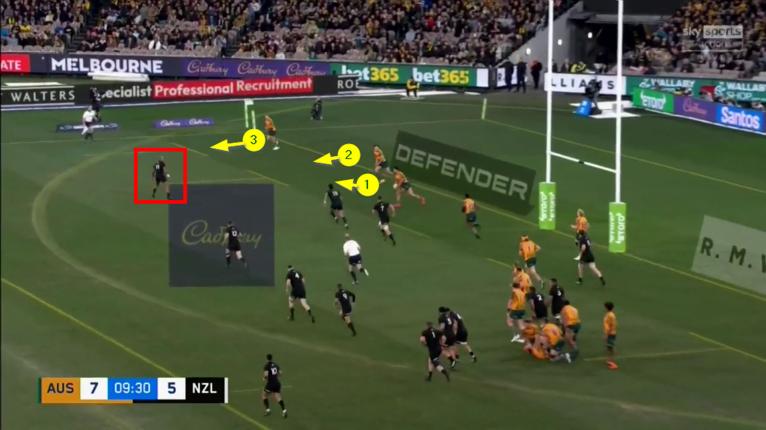

In this scenario, Carter Gordon is fully-justified in shifting the ball from his own goal-line by hand after a breakdown turnover by Will Skelton. The Wallabies No 10, and the full set of backs outside him can shift the ball with relatively little risk towards the right touch, where Mark Telea is momentarily isolated:

The best outcome would be a line-break in a thinly-defended area of the field, the worst a better kicking opportunity down the channel parallel to the right side-line. Instead Jordie Petaia looks to the boot immediately, and his short clearance gives the All Blacks a lineout feed on the Australian 22.

Compare that with New Zealand’s approach late in the second half:

There is no obvious overlap, but the All Blacks are prepared to work their way upfield and allow events to unfold – until either a gap opens, or the Wallabies make a mistake. Right wing Mark Nawaqanitawase duly obliges by flying out of the defensive line, and 30 seconds later the All Blacks were touching down in the opposite corner:

When he was encouraged to play himself into the groove with ball in hand, Carter Gordon looked the business. In only the fifth minute, Australia put together a 16-phase, one minute-50 second sequence starting from their own side of halfway, and Gordon’s ability to take the ball to the line aggressively became a factor:

Gordon pulls the defence towards him, that creates a small seam for Angus Bell to make a powerful second effort on the carry, and Nawaqanitawase exploits the widening split between the two sides of the Kiwi defence on the very next play. That’s how a drip becomes a gusher, and it’s how you build pressure with the ball in hand.

But whether by accident or by design, the Wallabies just do not do it nearly enough. They didn’t do it as much as any of their rivals in the Rugby Championship: they had the lowest figures for territory/possession, and they had the lowest stat for active time-of-possession at 14.7 minutes per game – six minutes less than their opponents last Saturday, New Zealand. That is a massive difference.

They set the fewest rucks, produced the lowest percentage of 0-3 second ball at the breakdown, made the most tackles and gave up significantly more penalties and yellow cards because of the constant pressure on their defence.

They scored the fewest number of tries in the truncated tournament (seven) at a rate of 2.3 tries per game – behind Dave Rennie’s average with the Wallabies in both the two previous years (2.8 tries per game in 2022, and 3.2 in 2021). At the Melbourne Cricket Ground in front of 83,000 hopefuls, the Wallabies won the first quarter by seven points to five, but lost the remainder of the match by a comparative landslide.

Are the Wallabies so far off-trend that they can only generate 20 minutes of constructive attacking play in an 80-minute game? Are they truly so far behind the times they cannot scent the musk of a possession-based style that they helped invent? Given Australia’s historical contribution to the attacking side of the game, it seems scarcely credible. At present, it is hard to disagree with Tate McDermott’s blunt summation at the end of the match: “83,000 people turned up tonight to support us, and we did not give them much.” The truth hurts.

Comments

Join free and tell us what you really think!

Sign up for free